Laura marker

Убежище (2020)

Recycled fabric, plastic, paint, found elements.

4.5Wx8x7.5 (inches)

For purchase inquiries and to learn more,

please contact the artist at www.lauramarker.co.uk

About the artist

Laura Marker earned an MA at Wimbledon College of Art. She primarily works with projection-based installation and digital collage. She is influenced by those concepts relating to the passage of time, visual “truth” and illusion, and past events or social injustices that still hold relevance today. Her work refers to historical developments in photography, science fiction imagery, historical scientific documentation and the development of new technologies, in particular lens-based technologies. She is particularly interested in how society reacts to these technologies. Lens-based technologies hold dual status, offering truthful observation on the one hand and fraud and illusion on the other. Magnifying lenses, magic lanterns, and cameras are associated with “penetrative” vision, capturing fragments of time too small for human perception to register, and with the capability to

uncover the unseen.

Transmission Series: The Final Transmission by Laura Marker.

All rights reserved.

The Entomologist’s Cabinet by Laura Marker. All rights reserved.

Portative Sight VI by Laura Marker. Sweet wrapper filter.

All rights reserved.

The Mycologist’s Daydream by Laura Marker. All rights reserved.

A Guide to Beetles by Laura Marker. All rights reserved.

To Time. To Flux. By Laura Marker. All rights reserved.

Transmission Series - Emergence by Laura Marker. All rights reserved.

First of All: night by Laura Marker, 2007. All rights reserved.

10 Days and Nights by Laura Marker. All rights reserved.

Artist’s statement

Убежище: (Noun): Asylum, refuge, shelter, haven, sanctuary, retreat.

Our face masks differ both visually and functionally from those adopted 100 years ago. Nearly everyone has an augmented-reality chip, making our eyes’ visual function unnecessary.

Early 21st-century versions of this technology still required

the wearer to make their own visual observations, but today’s technology interfaces directly with the brain, allowing the latest masks to cover the eyes entirely.

In 2120, nearly all thoughts, concepts, data, and emotions are communicated peer-to-peer via synthetic telepathy. This breakthrough has profoundly affected how personal information can be harvested, heightening the debate about the nature of individual privacy. In this society, only an individual’s appearance can now successfully be kept private . . . with a well-designed face mask. It has become quite fashionable to commission a mask that covers as much of the face as possible. The wearers often choose designs that hark back to a bygone world. Many adorn their masks with wondrous items from nature — seeds, flowers, shells or other artifacts — things once commonplace in the twenty-first century that are now increasingly rare. The most prestigious masks feature living elements rather than artificial constructions. The mask you see here is a simple example featuring dried flora, with textures and colors inspired by the wearer’s ancestral lands.

Laura Marker was our featured artist January 12-18. Here Laura shares further insights into her work.

10 questions

1.“Убежище” is spelled Ubezhishche in English and is the Russian word for “asylum.” Is there a particular reason you chose Cyrillic (Russian?)

I spent a long time deciding on a title for my mask, finally settling on Убежище which succinctly fitted the central themes of the work; a personal sense of asylum, refuge, shelter, sanctuary, providing a retreat from my imagined, futuristic world in which invasive technology has made a mask the only effective means to conceal your identity.

I found I liked the Cyrillic text better. Partially I just liked the way it looked on the page, but also the use of Cyrillic text kept the title and its meaning more hidden and obscured. Any non-Russian speaking viewer might ask themselves “what does it mean”? “is it an invented word, or is it real”? “what does that word even sound like?”

2. Some of your recent works such as Rotation, Portative Sight and Into the Curve deal with visual distortion via man-made items like lenses or metal tubes, but also can feature nature images of trees or outdoor environments. What do you want the viewer to take away with them after viewing these works and these elements of both visual distortion and nature?

It’s interesting that you have identified this juxtaposition between the use of made-made items as a means to capture and distort images that depict the natural world. Actually, my intention was more simply to bring back a sense of wonder and intrigue to the everyday world.

I have lived and worked in the same parts of London for many years and found that I was becoming somewhat blind to my surroundings. I simply wasn’t seeing the world around me anymore and had begun to lose that almost childlike sense of amazement and fascination when experiencing something for the very

first time.

I started trying to capture images from local walks, using low-tech, throwaway objects as a means to view reflections and distortions of the world around me. These objects have so far included a plastic globe shaped shampoo bottle filled with water, an old chipped magnifying lens, a reflective tube made of shiny black plastic (packaging), and a series I am currently working on that uses brightly coloured cellophane wrappers from low quality chocolates.

The subject matter was not very consciously chosen, but perhaps it’s inevitable for city dwellers to cling onto and focus on small elements of nature? For me, these works are more a playful investigation of the world around me, and allow me to re-access or “re-see” the world once again. I hope that the images allow the viewer to reconsider their own everyday environment, perhaps prompting a similar journey of discovery and experimentation.

3. Some of your works, such as The Mycologist’s Daydream, feature glass cases that enclose worlds made of collage and often featuring Victorian themes. Is this a reference to the Victorian mania for taxonomy and natural study, or are there other themes upholding these works?

I would say yes to both parts of this question. These works very much refer to the Victorian obsession for taxonomy and related developments and discoveries within the (natural) sciences but are also about the place of women within Victorian society.

I started these works straight after participating in a collaborative installation in a disused Edwardian Ladies Cloakroom (with artist Bethe Bronson) called Public Space: Private Women. This exhibition sought to investigate women's lives in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; a point in time where women faced many restrictions, but also a gradual increase in educational, leisure and professional opportunities.

After this exhibition I became fixated with the notion that many women throughout history must have been denied the opportunity to achieve their full potential due to societal constraints. I began to create a series of digital collages that used images of anonymous women from the nineteenth century, placing them within a tightly ordered and constrained taxidermy style setting. These women are at first glance what we expect nineteenth century women to be; they are decorative and they are “in their place”. However, on closer inspection, they are finding ways challenge the environment in which they find themselves.

This series has gradually developed, and now focusses on “missing women” from history; women who could have been our greatest scientists, explorers and innovators but due to a lack of opportunity could never take their place. Although there are some well-known women scientists, explorers and innovators from earlier centuries their number amounts to a mere handful when compared to men, so I have begun to create works that honour all of those that are absent from the history books (The Entomologist’s Cabinet and very recent works A Guide To Beetles and The Mycologist’s Daydream).

4. Can you tell us a little about your recent research work, Past technology - future vision: Occult illusion and optical truth in the imaginary technology of Hexen 2039.

In this research paper I discuss Suzanne Treister’s exhibition Hexen 2039 which was held simultaneously across five London venues in 2006. Hexen 2039 comprised a series of drawings, altered historical photographs and images of real historical artefacts. The premise was to explore an (imagined) occult-military technology research program that aimed to create a futuristic mind-alteration device. Treister approached this topic by intertwining visual imagery from a number of historical time-frames, through the eyes of her time travelling alter-ego, Rosalind Brodsky.

I was interested in the way in which Treister’s seamlessly amalgamated real artefacts and real documentary photographs alongside altered photographs and utterly invented elements to form new “realities” and new “truths”. By intertwining the futuristic, contemporary, historical and the “real” and “invented” Hexen 2039 engages with contemporary discourses relating to new and emerging technologies and the paranoia of state surveillance, alongside historical concerns that associated new technologies with the control of mysterious occult forces.

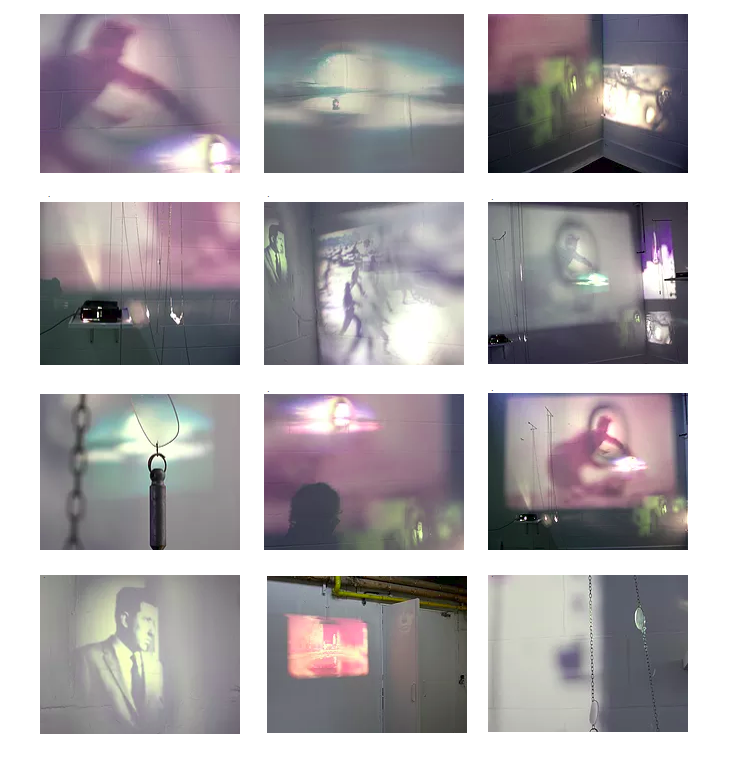

I used this research paper as a basis for a number of works including projection-based installation To Time. To Flux in which I used multiple defocussed 35mm slide projections, refocussing small elements using externally hung Perspex lenses. By montaging many different projected images and re-focussing small elements of each of these images it becomes difficult to isolate their true meaning. Instead of the soldiers, missiles and explosions that are contained in the majority of the chosen images, the viewer was more likely the observe a dreamscape or a phantasmagoria of deception.

5. What was the source of your inspiration for the visual path you chose when building Убежище?

I began by researching masks and breathing apparatus designed for sci-fi films and also historical masks, including plague masks of the seventeenth century and those worn at masquerade balls in the eighteenth century (masks that were specifically designed to obscure the wearer’s face). As we were in semi-lockdown at the time, I decided I should only use materials that I hand to hand, or that could be sourced on local walks. I ended up mainly using items destined for recycling such as old fabrics and plastic bottles and natural items such as seeds. Although the concept behind Убежище centres on a dystopian science-fiction vision of masks from the future, I knew didn’t want to make a classic sci-fi mask, but rather I wanted to create a mask that was both menacing and beautiful. something that hints of sci-fi but also of the past and something with an almost organic appearance, as if it may have evolved and grown over time.

6. It used to be that people accepted photographic images or film as proof of reality, undeniable evidence of the existence of a place, event, or people and their selves. While there have been ways of doctoring photographs that go back decades, now we have the technology to doctor photos to an undetectable extent. In particular I wonder how this evolution of image manipulation affects your sense of how to explore and represent the truth/illusion dual nature of the presented photograph or film? What is left that we can use as incontestable proof in a world where we rely almost entirely on the digital image, whether it is through the screen of our phone or the digital print on a billboard or poster, or a deep-faked film that is intended to deceive the viewer into believing something is true?

This is such an interesting question and I am not sure that I can do it full justice without spending a few more months considering the answer!

My interest in the evolution of photographic manipulation inevitably draws me back into the past as much as the present or future. I have spent a long time researching nineteenth and early twentieth century spirit photography (such as images produced by William Mubler) and pseudo-scientific documentary photography taken at seances under the guise of psychical research (such as images taken by Harry Price). Historical documents actually suggest that (very much like now) these historic doctored/faked images weren't necessarily taken at face value at the time, with many arguing against the veracity of photographs that appeared to provide evidence of the existence of spirits or of psychical activity. This research has led to consider the point that lies at the very heart between truth and illusion and also the moment at which Science and Pseudoscience collide. I like to make direct reference to these early faked and doctored images, as well as exploring these themes in a more general sense (Transmission Series and The Order of Things).

7. When did you first feel drawn to the properties of optics and light as a means of creating art? Do you have certain mentors or influences whose work made a particular impact on you?

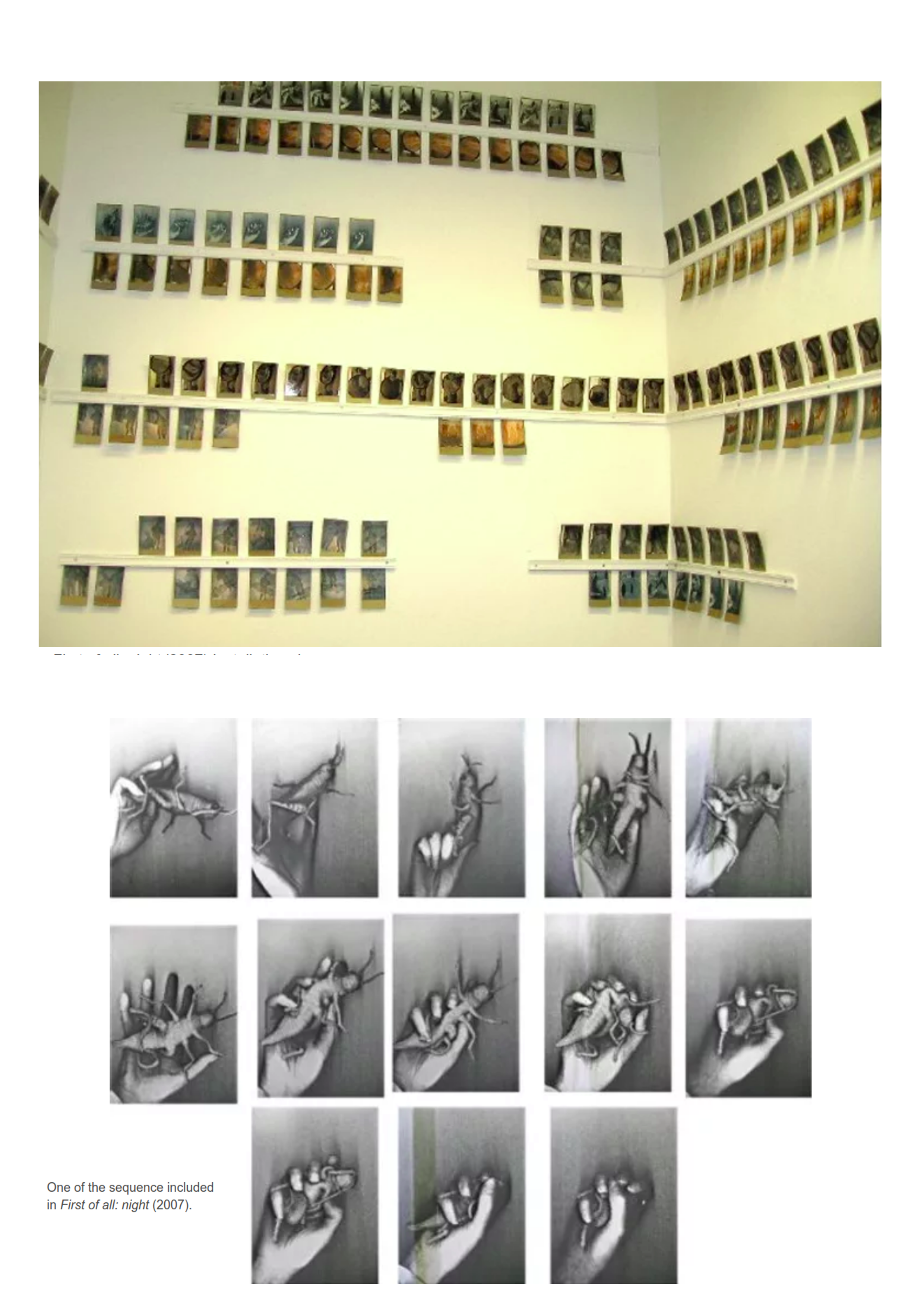

The first time I actively remember working in this way was for an installation called First of all: night (2007). This installation comprised multiple photographic sequences exploring the methods torture utilised by the Soviet state as outlined by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago. At the time the world was very focussed on Guantanamo Bay and the Iraq War so Solzhenitsyn’s book held an eerie resonance, like terrible aspects of history were repeating over-and-over again.

I produced numerous image sequences (like animations presented as stills) that explored different aspects of interrogation process. These image sequences made use of projections, shadows, photographs of images distorted with the use of a magnifying glass etc. These photo sequences were heavily influenced by the nineteenth century photographer Eadward Muybridge’s sequence images.

Although I am influenced by many artists, I also look beyond traditional art settings, so you will just often find me in museums (the modern-day version of a cabinet of curiosity), or researching science fiction imagery, or old photographic processes, old newspapers, or observing photography and illustrations that document real scientific discoveries from the past.

8. Your work spans and combines many media: installation, photography, sculpture, and collage. How do you answer when someone asks “what kind of art do you make?”

If only I had a good answer to this one! I think it really depends on who I am talking to. Many people look quite disappointed or confused when they discover I don’t usually paint or draw. I usually resort to saying that I work with mixed media and end up trying to explain that I work a bit with photography, film, digital media and projection and digital collage and projected artwork. It is getting easier, as installation/video art in particular has had a higher profile in recent years.

9. Part of Убежище is rooted in the fear of and defense against total observation: we are under the eye of obvious and hidden cameras in a hypothetical world 100 years hence, to the extent that as you describe that future, our most prominent identifying and expressive feature – our faces – are permanently covered and we have lost the need for direct observation since we now have instrumentation that allows us to perceive everything we need to. How close do you think we already are to that level of scrutiny from anonymous cameras, and in your opinion, are we reacting at all to that imbalance of scrutiny? How do you think we are being affected by this particular power differential?

I think we are certainly getting there! We are living in a time where surveillance technology is rapidly developing and cameras are one of the most direct and most easily recognisable instruments used in the surveillance of society and of the individual. We have lived with these CCTV cameras for some time, so it’s easy to overlook the ways in which they are changing, such as utilising facial recognition software to identify individuals in a crowd. The technology has become inexpensive, ubiquitous and is as much part of the suburban street as it is a shopping centre, airport or train station.

Today we already leave a breadcrumb trail of our presence whether our faces are covered or not. When we drive, the registration plates of our cars are captured by automatic number plate recognition devices whilst even the most basic of mobile phones leave logs that show which towers they were connected to so we are constantly tracked and monitored by machines.

Contemporary surveillance now goes well beyond the state and into the hands of powerful companies. Our perception of reality is now filtered through algorithms that decide what our news feeds should contain, what adverts are appropriate for us. Social media companies utilise facial recognition software, hold all the information we have ever posted, which for some can be their deepest held options and thoughts. We have a choice whether or not to actively use social media, but to opt out is beginning to be seen as strange, and potentially suspicious behaviour.

Legislation has been slow to catch up with these changes so we lack adequate protections as to what the collected data is used for. We really need to be asking “who do we trust with access to this data”? “Who should be keeping this data, and how much of it and for how long”? This technology only remains as safe as the intentions of those behind it and history teaches us that governments can change, and not all are to be trusted.

10. What advice would you offer to someone just beginning their artist career? What can you tell them that you wish you had known when you were starting out?

I came to art a little later than some, having initially studied music. I think I would tell someone just starting to follow their heart and not to worry about being good enough. Art is as much a personal journey in which you constantly develop and evolve as anything else. Keep on doing what you love doing, have the courage of your convictions and it’s never too late to change directions. Not everyone will like or understand what you are doing, but that’s okay!